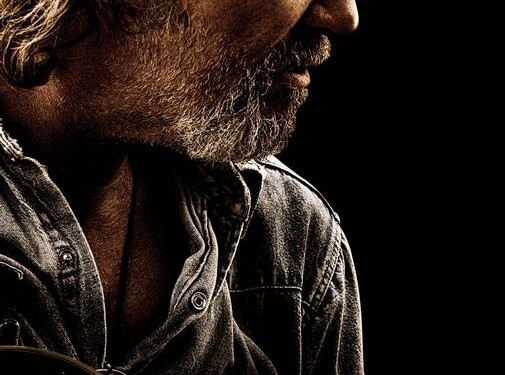

Crazy Heart (Movie Review)

12.16.2009 | By Terry Kim |

Crazy Heart is an underdog story—and an underdog story a few decades overdue, to be exact—about a fifty-seven year-old country singer, Bad Blake (Jeff Bridges). Blake is broke, has a twenty-eight year-old son he hasn’t seen since he was a toddler, and has a severe drinking problem. To top it off, he falls in love with a small-town reporter, Jean (Maggie Gyllenhaal), while performing in Santa Fe. Feeling a tad more reinvigorated from his new love, he decides to pick things up a bit, and slowly puts pen to paper after years without song writing. Just when he thinks things are looking its best, he hits rock bottom yet again: while baby-sitting Jean’s son at the mall, he loosens up with a drink at the bar, and loses sight of the kid in the process. After the mall ordeal, Jean storms off, leaving Blake all alone. After a few days of wallowing, Blake checks himself in to rehab, and finally finishes the songs he has been putting off for all those years. He finally accepts the fact that although he may no longer occupy center stage, he is happy knowing that his protégé, Tommy Sweet (Colin Farrell), will take over in his place.

Jeff Bridges has been nominated for four Oscars, and it is the sincerest wishes of many that he will take home his lucky fifth. I cannot help but compare the story, and Bridges’ performance to last year’s The Wrestler, in which Mickey Rourke also played a world-weary man, looking for a way back in. Crazy Heart does not boast any fancy camerawork, so Bridges’ acting inevitably steals the spotlight. One can almost smell the whiskey from off screen, as he lugs himself around dusty motels. He is also personally invested as one of the executive producers of the film. Robert Duvall also appears in the film as Blake’s old friend, and is one of the producers as well.

Crazy Heart is an honest tale about how it is never too late to get your life back on track, and about taking your trials and tribulations and channeling them through an art form, like music. All music was done by T Bone Burnett, who is a music producer renowned for soundtracks like O Brother, Where Art Thou?, Cold Mountain, Walk the Line, and The Big Lebowski. It is interesting to hear some of Blake’s songs repeated throughout the film, a realistic depiction of the redundancy entertainers are subjected to; indeed, some of the live performances, whether they take place in bars or bowling alleys, begin to weld together so that they are indistinguishable from one another.

Coupled with the raw landscape of the American Midwest and the mellifluous country music, Crazy Heart is not only recommended for all y’all boots-toting cowboys out there, but for anybody suffering from heartache and mental blocks, and could use a buoyant story about an old dog that can learn new tricks.