The ‘buzz’ surrounding Mexican cinema

03.7.2009 | By Mack Chico |

We have seen it at football grounds. The crowd heaves in a rise and fall, a giant moving undulation that someone, somewhere, for some reason, dubbed the Mexican wave. Maybe it’s because Mexicans do things big. They grandstand when they come to town. They put their hearts, minds, souls and body language into a thing.

Consider a Mexican wave bigger than any other in recent times. The movie wave: Like Water for Chocolate (1991), Cronos (1993), Y Tu Mamá También (2001), Pan’s Labyrinth (2006). And larger in impact than any, Amores Perros (2000). Guillermo Arriaga, the writer of that film, a brilliant, brutal set of stories about passion, poverty and obsession, went on to write 21 Grams (2003), Babel (2006) and The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada (2006). It is a screenplay oeuvre that merits, for some fans, a Latin American art throne alongside Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa and Jorge Luís Borges.

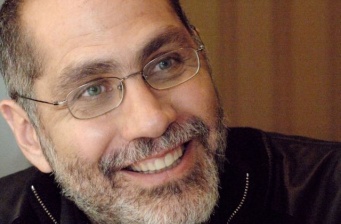

Guillermo Arriaga’s new film is directed as well as scripted by him. The Burning Plain (released in the UK next week) is a typical arson attack on the viewer’s mind and senses from a man who, when I meet him in a London hotel, seems to have emerged from a minor furnace himself: a smoky, pale-tanned 50-year-old, slim of frame with a thinning stubble of hair. That he also has luminous, El Greco eyes and speaks accented, mellifluously persuasive English may explain how he beguiled two A-list Hollywood actresses, Charlize Theron and Kim Basinger, into starring in a film about self-mutilation, cancer, violent death and childhood trauma.

The plot and its payoff are ringed with “don’t reveal” security tape. Enough to say that the parallel stories of quest set in Mexico/New Mexico and Oregon – quest for love, truth, ancestry, destiny, quest for the consummations that may also destroy us – explore and expand Arriaga’s favourite metaphor for the human condition. Hunting.

“We are all hunters and stalkers. We come from hunting genes. It’s what defines the human race. For me, it’s my antidote against alienation.” Another antidote is cinema and the innovative story structures he began to fashion in the three films made with director Alejandro González Iñárritu. The jigsaw patterns of Amores Perros, 21 Grams and Babel have influenced virtually every succeeding movie with a globalist reach, from Syriana to The International.

Arriaga doesn’t fashion these structures to be difficult. “I want the audience to be actively engaged in the story”, he says, “and sometimes, when you take the logic out of storytelling, people get involved emotionally rather than rationally. They start to trust their feelings. At the same time it allows the audience to fill the gaps with their own story, their own imagination.”

Since he founded a virtual new storytelling tradition in cinema, it is easy to understand Arriaga’s anger when Iñárritu retreated from a claimed agreement to share credit. “The problems began early on after we made Amores Perros. I am not a writer for hire. I do not ‘work for’ a director. These are original stories and when Alejandro began to say, ‘This is my film’, I said, ‘This is not what I think is right.’ We didn’t share the original creative vision. These are personal works that come from my own life.”

They split up before Babel began shooting. Will they work again? “Never. Never. The ways are parted.”

He found another soulmate, for one project at least, in the actor-turned-director Tommy Lee Jones. The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada – for me Arriaga’s best film – is a burnished tale of revenge and redemption, turning on a man’s violent death and the pilgrimage of his friend (played by Jones) to bury him in his native Mexico.

The US-Mexican border, with all that it implies about neighbourhood and division, is at the heart of Arriaga’s new trilogy, whose first two parts have taken shape in Three Burials and The Burning Plain. The third part, The Deer’s Sun, set in Texas and across the border, will be about the death penalty.

“We cannot forget that the American south-west was once part of Mexico,” Arriaga says. “It still has Spanish names – Los Angeles, El Paso. So there is this strange relationship between the countries.”

Strange and strained, I say. Everyone seeks a solution, no one finds one. “The solution is very easy,” he says. “Mexico needs work, the United States needs the workforce. Mexicans need to be able to work and go back.

“People get crazy with jealousy,” he elaborates. “My friend Melquiades Estrada – he’s a real person: I named the film in homage to him – met his daughter when she was nine. He left Mexico when his wife was pregnant to live and work in the US. Meeting your daughter when she’s nine, that’s heartbreaking! And every month you send home money to a wife you don’t know is still faithful. And the woman at home thinks, ‘Is he in love with someone else?’”

This pondering of connection or disconnection across spaces, the biggest theme in Arriaga’s stories, touches in turn on the biggest theme in contemporary discourse – globalisation, the linking leitmotif in Babel.

“We cannot be naive. Globalisation is happening, we can’t stop it. But the concept of nationhood is very young. The USA is 250 years old. In terms of humanity, that is almost nothing. Six hundred years ago, Spain was dominated by Arabs. So what defines nationhood?”

Something, some would say, like the Mexican New Wave in cinema. Identity through art. But even this happy convulsion, Arriaga says, was a fluke of history. “In Mexico we had an economic crisis that prevented a whole generation from shooting films. So it was like a boiling culture that was waiting to explode.”

As for a distinctive “Mexican-ness” in his country’s cinema, he starts by waving away the generic cliché for Latin American narrative art. “Magic realism no longer exists. Even García Márquez did it in such a way as to leave nothing for others to take up.” Then he says art is about individual voices, not national ones. “Look at some of the novelists who represent the United Kingdom. Hanif Kureishi. Kazuo Ishiguro. Are they ‘British’?”

He remembers, illustratively, the first conversations he had with Tommy Lee Jones. It was, in the best sense, a dialogue of the deracinated. “He rang me out of the blue, speaking Spanish. ‘ Hola, Guillermo! … I saw Amores Perros’, he said, ‘and I would like to work with you. Where are you?’ I’m in León. ‘Let’s have dinner.’ We met and since I was going to write for him, we quizzed each other about our tastes. Who is his favourite filmmaker? Kurosawa. He asks me who is my favourite novelist. Cormac McCarthy. Favourite painter? Edward Hopper…”

Thank goodness for film, the common language of the world. And thank goodness for filmmakers, who know that in the arts, at least, the border crossings are open for business.