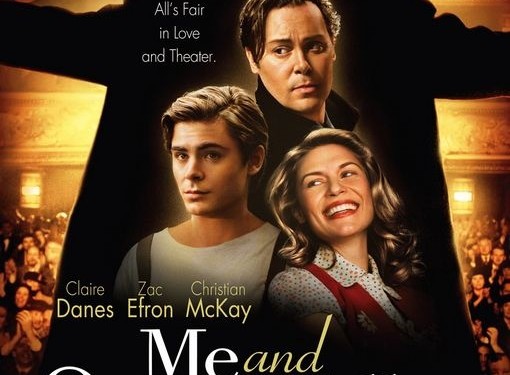

Me and Orson Welles

11.21.2009 | By Terry Kim |

For those who recognize the name in the title of Richard Linklater’s latest film may have an immediate attraction (or immediate aversion) to it. After all, Orson Welles always lands itself in critics’ “top filmmakers of all time,” and his Citizen Kane (1941) makes it in “top ten most influential films” lists. Older generations may remember Welles from his radio days, and still others may remember him from his famous television commercials of the 70s. I’m willing to bet that members of the younger generation will watch this film in recognition of the High School Musical series heartthrob, Zac Efron (who plays the part of starry-eyed teenager Richard), the “me” in the title.

Me and Orson Welles is about seventeen year-old Richard, who is employed by Orson Welles to play a minor role in his first show at the Mercury Theatre, Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. Richard and Welles get along for the most part—Welles even takes Richard to a radio studio, gives him a lift on his ambulance (the only way to wade through traffic in Manhattan), and affectionately calls him “junior”—until Richard falls for Sonja Jones, an assistant who is beautiful yet unapologetically ambitious. Sonja merely wishes to get ahead in life, and is unconcerned with love, art—basically all the ideals Richard identifies himself with. After a week of success and failure, love and heartbreak, Richard is ready to return to a less exhilarating, yet more wholesome, high school life.

Linklater—who made his name with the high school movie, Dazed and Confused (1993), and for the Before Sunrise/Before Sunset pair (1995 and 2004, respectively)—takes a somewhat different approach in Me and Orson Welles. The film is essentially a bildungsroman in 1937 New York, and therefore a period piece as well. The background is rather convincing: Linklater, along with production designer Laurence Dorman, handpicked the theater to pose as the then-Mercury Theatre, and he also selected the music, since he is a huge fan of 30s music. The film is indebted to the pre-existing material in Robert Kaplow’s novel, which he based in real theatrical history. Especially convincing is Christian McKay’s impersonation of Orson Welles, which is spine-chillingly identical.

The film can be most respected for its frankness, because it doesn’t dare to over-glamorize Welles, the Mercury Theatre, or the city, but only to see the aforementioned things through a naïve teenage boy’s eyes; think of it as a week-long orientation to the Big Apple. Linklater’s style is also equally simple: instead of relying on fancy computer editing, for example, he uses what I’d like to call “manual” montage (Richard catching bits of conversations as he walks through the opening night party scene; Richard flipping through newspaper headlines on Caesar). Welles is portrayed as the charismatic man he was known as, but we also glimpse moments of sensitivity, and it isn’t easy to simplify him as a heroic character or a villainous one. Perhaps a weaker delineation is that of Gretta (played by Zoe Kazan), and particularly her parallels to Richard. As they exit the museum, the two find themselves in differing paths of progress. This is, of course, the way things are: a writer is suddenly jet-set with her submission to The New Yorker (Gretta), and an aspiring actor performs only on the opening night of an anticipated production (Richard). Their sudden bonding at the end seems a bit contrived, however.

This film is a must-see for New Yorkers, would-be New Yorkers, good music, and anybody who wants to see the most accurate impression of Orson Welles to date.