07.25.2008 | By Alex Florez |

*Updated December 2025

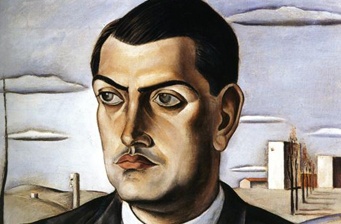

The Retrospective at the Berlinale this year was devoted to Luis Buñuel, an odd choice perhaps for the German capital, but exceedingly valuable. It offered viewers not only the familiar surreal landmarks of the 1920s and those from the end of his long career, but also a look at just about everything that came between, when the director was earning a living churning out all sorts of films in France, Spain, Mexico, and the US as producer, uncredited director, and writer.

Many of these have been forgotten, or certainly neglected, and sometimes for good reason. The stage transformations Buñuel produced in Madrid, like Don Quintín el Amargao, had virtually zero theatricality or cinematic interest, and bore the unmistakably primitive look of mid-1930s pre-fascist Spanish features.

The anti-fascist Spanish documentaries Tierra sin pan (1933) and España 1936 forced the director to the US and then to Mexico, where conditions stylistically and financially improved under the producer Óscar Dancigers.

But not right away. Gran Casino (1947) was a routine musical, barely melodramatic, but at least showcasing singers Jorge Negrete and Libertad Lamarque as a fairly unlikely pair of lovers. By 1950, with Los Olvidados, the socially-conscious and dramatically-surprising Buñuel, with the stunning images of cameraman Gabriel Figueroa, was propelled back to international acclaim via Cannes.

The Mexican 1950s produced masterworks like Él and Nazarín, but also such films as a remake of Don Quintín (La Hija del engaño, 1951), a Maupassant adaptation (Una Mujer sin amor, 1952), a version of Wuthering Heights, and the rather pallid social melodrama El Bruto (1953). The latter at least had Katy Jurado slicing off some flower tops in an assassination fashion.

There was also the fairly languid, unfeverish political drama La Fièvre monte à El Pao (1959), a co-production with France starring the miscast but otherwise gorgeous couple Gérard Philipe and María Félix. La Joven (1960) was a bizarre mixture of Robinson Crusoe, The Defiant Ones, and Lolita, marked by at least one Buñuelian fetish, high heels, and Figueroa’s stark photography.

The titles from the 1960s, from France, Italy, Mexico, and an ultimately forgiving Spain, all offered their more familiar, discreet, obscure, fantasmic, anti-clerical Buñuelian charms: Viridiana, El Ángel exterminador, Le Journal d’une femme de chambre, Simón del Desierto, Belle de Jour, and Tristana, up to the culmination of his career, Cet obscur objet du désir in 1977.

Apart from the Buñuels, handsomely arranged by the Berlin Kinemathek curator Rainer Rother, the Berlinale had further delightful surprises on hand. There was a tribute to Italy’s Francesco Rosi. The print of perhaps his most celebrated film, Cristo si è fermato a Eboli, had its color so browned-out that it seemed almost intentional in its view of scorched southern Italy.

Among the restorations were The Belle of Broadway, produced for Columbia by Harry Cohn in 1926. This had Betty Compson in a dual role, as a Parisian theater star in the 1890s and an American girl thirty years later, in a story that anticipated elements of Evergreen (1934) and Madame X (1929). Die Gezeichneten, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer in 1922 (and newly restored by the Danish Film Archive), depicted a Russian pogrom in 1905.

It was all the more chilling as it was filmed entirely in and around Berlin, well before 1933. The sets were convincing, the performances striking, and the film had the invaluable accompaniment of Maud Nelissen at the piano, plus accordion.

Ms. Nelissen also led a contingent of the Komische Oper orchestra in her new score for an entirely non-Berlinale showing of Erich von Stroheim’s The Merry Widow (1925). Lehár’s score was admirably synthesized into something quite as original as Stroheim’s eccentric take on the operetta, and the result (thanks also to a nice print from Vienna) was easily a highlight of this Berlin visit.

MGM’s massive production, with Stroheim’s obsessive Habsburg detailing, the spectacular sets and costumes (Cedric Gibbons and Richard Day), and the astonishing matte and glass shots outflanked much of the purported opulence of Metro in the 1930s. The pre-1914 Balkan atmosphere was so realistically charged that the assassination of a crown prince became almost inevitable.

Any residual operetta glamour came from the expert playing of Mae Murray and John Gilbert, reaching a climax in their voluptuous waltz-tango at a Parisian ball, surely one of the most enduring cinematic souvenirs of the 1920s.